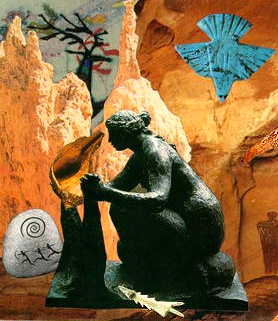

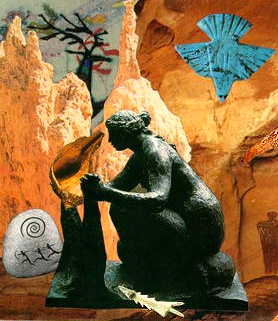

Some 50,000 years ago -- a mere1 drop in the evolutionary bucket2 -- women were gathering3 while men were hunting. This primeval4 division of labor is the wellspring5 of many of the behavioral oddities6 that separate the genders7 today.

Some 50,000 years ago -- a mere1 drop in the evolutionary bucket2 -- women were gathering3 while men were hunting. This primeval4 division of labor is the wellspring5 of many of the behavioral oddities6 that separate the genders7 today.

Paleolithic women, who were nursing8 their youngest children and trying to keep tabs9 on the others, became accustomed10 to multi-tasking early on. The best of them -- who thus became the breeding stock11 for all of us females -- could scope out12 hidden roots and berries13, give suck14 to an infant and keep half an eye on the toddler15 wandering off16 toward the cliff edge or the wolf den17, all the while carrying on a good, gossipy18 conversation with her best friend from the cave19 next door.

Meanwhile, her mate was off on a three-day run after an edible20 quadruped21. He needed to maintain his focus and conserve his energy if he wanted to bag22 his quarry23 -- no gossiping or multi-tasking allowed.

That's why men today are so much better able to compartmentalize than women. When a man's at work, he's at work. He doesn't go in to work and think about the painful conversation he had last night after dinner with his wife or talk about said24 painful conversation with a colleague at lunchtime.

On a hunt, Paleolithic men related25 to each other side-by-side, not face-to-face across a berry patch26. Instead of focusing on each other, they focused on the muscular exertions27 of another mammal.

On a hunt, Paleolithic men related25 to each other side-by-side, not face-to-face across a berry patch26. Instead of focusing on each other, they focused on the muscular exertions27 of another mammal.

And so a modern-day woman wants to sit across a table from her husband at an Italian restaurant, whereas her husband would feel far more comfortable sitting next to her watching a sporting event on TV.

The strongest males learned to go for long periods of time without eating -- however long it took to run their prey28 to ground, get close enough to skewer29 it with a spear30 or bean31 it on the head with a rock. When they did eat, they gorged32 themselves and then rested33 before bringing home the leftovers34 to the wife and kids.

The adult female would graze35 as she gathered, not only to keep her strength up but also to take note of where the sweetest berries came from and which roots and leaves seemed to hold medicinal properties.

When the human genome is fully mapped36 and deciphered37, I predict we'll find a suite of genes in females -- bred for eons to graze rather than gorge -- that calls for frequent but light meals. The most thoughtful of modern-day males always take this into consideration while in the company of females: Women need to refuel more often than men or else they get lightheaded38 and bitchy39.

Women, on the other hand, need to understand that a quick snooze after a big meal exerts an irresistible attraction for many males of the species. It's not a comment on his companion's charms or the quality of her conversation; it's just what his cells are commanding him to do. He who has hunted must have his sleep.

Finally, there's the phenomenon comic Rita Rudner refers to as "refrigerator blindness40" (my friend Liz Stonehill refers to it as MPB -- "male pattern blindness."). Men, who are after all programmed to keep their eyes on things that are running away from them, tend to have trouble finding anything that's not moving. If it's a slightly camouflaged berry or root -- or another item of nonambulatory food stationed, say, behind a half-gallon of milk in the fridge -- chances are the man won't be able to see it.

It takes more than a measly41 50,000 years of evolution to change the genetic adaptations of millions of years. One set of adaptations isn't better than the other; obviously, both were needed to ensure the continuation of our species. Maybe we need to think more about the sort of teamwork that will capitalize on the strengths and bolster42 the weaknesses inherent in each gender.

Male and female, we are what we were, and we'd all get on with a lot more grace and good will43 if we kept this in mind.

myprimetime

Some 50,000 years ago -- a mere1 drop in the evolutionary bucket2 -- women were gathering3 while men were hunting. This primeval4 division of labor is the wellspring5 of many of the behavioral oddities6 that separate the genders7 today.

Some 50,000 years ago -- a mere1 drop in the evolutionary bucket2 -- women were gathering3 while men were hunting. This primeval4 division of labor is the wellspring5 of many of the behavioral oddities6 that separate the genders7 today.